Английский - простой, но очень трудный язык. Он состоит из одних иностранных слов, которые к тому же неправильно произносятся.

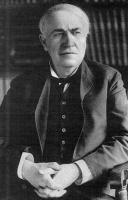

THOMAS ALVA EDISON 1847-1931

When Thomas Edison was born in the small town of Milan, Ohio, in 1847, America was just beginning its great industrial development. In his life of 84 years, Edison shared the excitement of America’s growth into a modern nation. The time in which he lived was an age of invention, filled with human and scientific adventures, and Edison became the hero of that age.

As a boy, Edison was not a good student. His parent took him out of school and his mother taught him at home, where his great curiosity and desire to experiment often got him into trouble. Once he set fire to his father’s barn “to see what would happen”, only to have the barn burn down.

When he was 10, Edison built his own chemical laboratory. He sold sandwiches and newspapers on the local trains in order to earn money to buy supplies for his laboratory. His parents became accustomed, more or less, to his experiments and the explosions, which sometimes shook the house.

Edison’s work as a salesboy with the railroad introduced him to the telegraph, and with a friend, he built his own telegraph set. Though partially deaf because of an injury, which he had suffered while selling candy on the train, he could hear the click of the telegraph and chose to specialize in telegraphy. He taught himself the Morse Code and hoped for the chance to become a professional telegraph operator. A stroke of luck and Edison’s quick thinking soon provided the opportunity.

One day as young Edison stood, waiting for a train to arrive, he saw the station master’s son wander into the track of the approaching train. Edison rushed and carried the boy to safety. In gratitude, the station master offered to teach Edison railway telegraphy. Afterwards, in 1863, he became an expert telegraph operator and left home to work in various cities.

Six years later, in 1869, Edison arrived in New York City poor and in debt. He went to work with a small company that later became part of the Western Union Telegraph Company. It was here that he became interested in the uses of electricity. At that time, electricity was still in the experimental stages, and Edison hoped to invent new ways to use it for the benefit of people. As Edison once said: “My philosophy of life is work. I want to bring out the secrets of nature and apply them for the happiness of man”.

In 1869, when he was only 22 years old, Edison invented an improved stock market ticker-tape machine, which could better report the prices on the New York Stock market. The ticker-tape machine was successful, and Edison decided to give up telegraphy and concentrate wholly on inventing. When the president of the company asked how much they owed him for his invention, Edison was ready to accept only $3,000. Cautiously he asked: “Suppose you make me an offer”. The president responded, “How would $40,000 strike you?” Edison almost fainted, but he finally replied that the price was fair. With this money, and now calling himself an electrical engineer, Edison formed his own “invention factory” in Newark, New Jersey. Over the next few years, he invented and produced many new items and improvements of the telegraph.

In 1877, Edison decided he could no longer continue both manufacturing and inventing. He sold his factory interests and built a new laboratory on an estate in Menlo Park, New Jersey, which was the first laboratory of its kind devoted to organized industrial research. He equipped his laboratory with good scientific instruments and one university-trained mathematician. He announced that his invention factory would be turning out inventions every few days — even “to order” — and then made good his promises. What Edison had succeeded in doing was to make a business of invention.

One of the first inventions to come from their new laboratory was an improvement on Bell’s telephone. Edison invented a more powerful mouthpiece, which eliminated the need for shouting into the telephone, but his great inventions were still to come.

On August 12, 1877, Edison began experimenting with an apparatus, which he had designed and ordered to be built. It was a cylinder, wrapped in tin foil, turned by a handle, and as it revolved a needle made a groove in the foil. Turning the handle, Edison began to shout, “Mary had a little lamb, whose fleece was white as snow!” He stopped and moved the needle back in the starting position. Then putting his ear close to the needle he turned the handle again. A voice came out of the machine: “Mary had a little lamb, whose fleece was white as snow!” Edison just invented the phonograph, a completely new concept: a talking machine.

While he was perfecting his phonograph. Edison was also working on another invention. He called it “An Electric Lamp for Giving Light by Incandescence”; he called it the lightbulb.

For years other inventors had experimented with electric lights, but none had proved economical to produce. The carbon “arc” lamp had been invented in 1877 and was highly successful for street lighting, but the “arc” lamp gave off a brilliant flame and was too bright for household use.

Edison, in studying the problem, spent over a year in testing 1,600 materials (even hairs from a friend’s head) to see if they would carry electric current and glow. Finally, on October 21, 1879, he tried passing electricity through a carbonized cotton thread in a vacuum glass bulb. The lamp gave off a feeble, reddish glow, and it continued to burn for 40 hours. Edison’s incredible invention proved that electric lighting would be the future light of the world.

Edison was now so famous as an inventor that people thought there was nothing he could not do. They began to call him the “wizard” as if he could produce an invention like magic. Few people realized how hard Edison worked — often 20 hours a day — and that most of his inventions were the results of hundreds of experiments.

No one but Edison knew how hard and long he had worked to achieve his great victory with the light bulb. Nor did he stop there. He not only developed an improved dynamo to provide the power for electric lighting, but he also perfected other electric power equipment such as generator, conductors, and underground power cables. The carbon filament lamp and the system of electrical distribution, which he devised were very developments in the modern electronics revolution.

As a result of this revolution, masses of people throughout the world were released from their dependence on oil and gas lamps for light. The enormous steam engines, long used for power in factories, now could be replaced by a more practical power turned on with a switch.

In 1887, Edison moved his laboratory to larger quarters where he employed an even larger corps of research assistants. The fluoroscope, the storage battery, the dictating machine, and the mimeograph were all products of collective invention coming out of this laboratory. Edison had carried out a transition in 19th-century science from the individualistic way of invention to that of specialized teams engaged in systematic research.

For more than 50 years Thomas Alva Edison was the world’s leading inventor. He patented over 1,000 inventions, which changed our ways of living.

He designed the central power station, which became the model for the first public electric plant in New York City, providing electric power for thousands of homes and businesses. Edison was one of the earliest inventors of the motion-picture machines. His invention of phonograph was joined with photography to produce talking pictures. He also perfected the electric motor, which made streetcars and electric trains possible.

Therefore, it is no wonder that Edison received many honours during his life for his contributions to the progress of mankind. America bestowed on him its highest award, a special congressional Medal of Honour. Yet, Edison remained a modest man. He preferred to continue his work rather than rest on his achievements. His motto was: “I find what the world needs; then I go ahead and try to invent it”. He never considered himself a brilliant man and once remarked that genius was “two percent inspiration and 98 percent perspiration”.

When Edison died in 1931, it was proposed that the American people turn off all power in their homes, streets, and factories for several minutes in tribute to his great man. Of course, it was quickly realized that such a tribute would be impossible, and its impossibility was indeed the real tribute to Edison’s achievements. Electric power had become so important and vital a part of America’s life that a complete shutdown for even a few seconds would have created chaos. As “one of the last great heroes of invention”, Thomas Alva Edison rightfully belonged to among America’s and the world’s great contributors to industrial development and progress of man.